The only things left to do for these medications to become FDA-approved diabetes therapies are testing and reapproval.

Currently, a couple of medications that are used to treat cancer may eventually find their way into the treatment regimens of some individuals who have diabetes. Small molecule inhibitors GSK126 and Tazemetostat have been shown to have the potential to be repurposed for the goal of stabilizing insulin production in individuals who have type 1 diabetes, according to recent study that was led by the Baker Heart and Diabetes Institute in Australia. Furthermore, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has previously granted approval for these medications, which means that there are fewer issues regarding the inherent hazards associated with them.

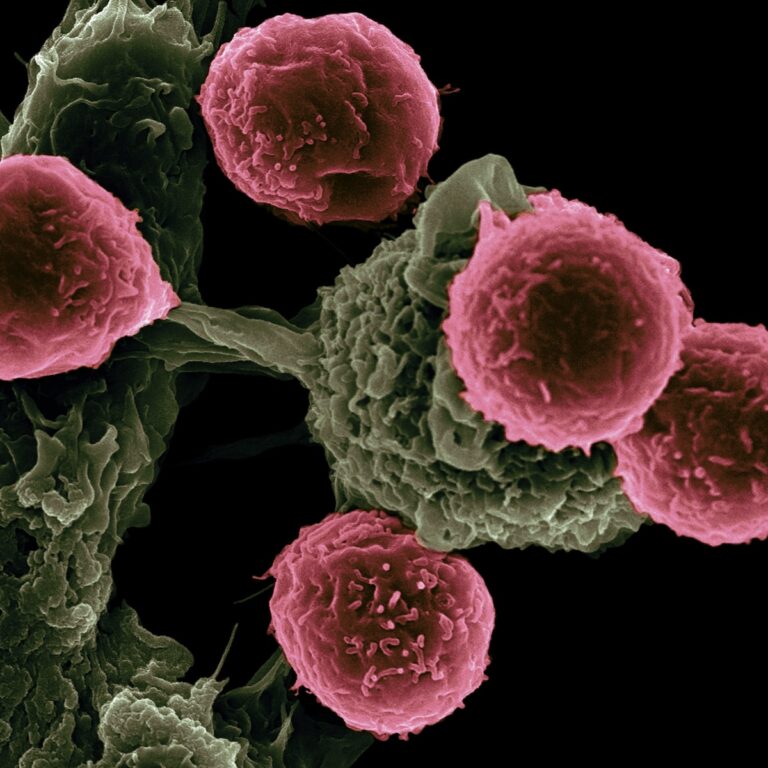

One of the characteristics of type 1 diabetes is the absence or inactivity of β-cells, which are normally located in the pancreas. Insulin, which is essential for the body’s ability to convert glucose into energy, is produced by β-cells, which are responsible for their production. People who have type 1 diabetes are need to inject themselves with insulin numerous times per day for the remainder of their lives because they do not have sufficient “natural” insulin. The majority of people who have type 1 diabetes find it challenging to keep their blood sugar levels at the required ranges because not only is it bothersome to manage throughout the day-to-day lives of patients, but it is also tough to afford.

GSK126 and Tazemetostat, on the other hand, have the potential to restore the body’s ability to produce insulin. Researchers have written in a report that was published on January 1 that both medications, which are now being used to suppress the growth of tumors in people who have cancer, target the EZH2 enzyme that is found in the human body. The process by which the body “decides” what an immature cell will develop into is referred to as cell destiny determination, and this enzyme is involved in that process. When the function of EZH2 is inhibited by GSK126 and Tazemetostat, immature cells in the pancreas, which are referred to as progenitor ductal cells, appear to assume responsibilities that are comparable to those carried out by β-cells.

The Baker Heart and Diabetes Institute discovered, through collaboration with universities in Melbourne and Hong Kong, that altered progenitor ductal cells not only produce insulin but also sense the glucose levels in the body and change their insulin production accordingly. The researchers observed that the use of GSK126 and Tazemetostat to partially block EZH2 encouraged the body to produce and control insulin within forty-eight hours. The participants in the trial were two patients with type 1 diabetes, one of whom was seven years old and the other of whom was sixty-one years old. The age difference between the two people is an encouraging sign that GSK126 and Tazemetostat can perform as diabetic therapies over a wide range of age groups. This is despite the fact that the cohort only consists of two participants.

Currently, the use of GSK126 and Tazemetostat is restricted to patients who have been diagnosed with lymphoma and colon cancer. This is because FDA clearances stipulate the conditions under which a medicine can be administered. As a result, neither medication is currently suitable for use in the treatment of type 1 diabetes. As is the case with any “new” medicine, both medications will be need to go through clinical testing as diabetic therapies before the Food and Drug Administration will provide their approval for use in this capacity. However, the fact that their hazards are mostly understood is a heartening omen.